Myerson came under fire for oversharing her child’s life, with a now infamous TV interview with the ever-acerbic Jeremy Paxman mansplaining motherhood to a very nervous (and gracious) Myerson, whose only defense seemed to be, “But he’s my boy!”

That book, in this reviewer’s opinion, was massively misunderstood, brilliantly mixing the story of Myerson’s investigation of a young girl from the 1800s who died before she could be a woman, and Myerson’s own childhood. All three could be the eponymous lost child. If it were published now, it would be labeled autofiction.

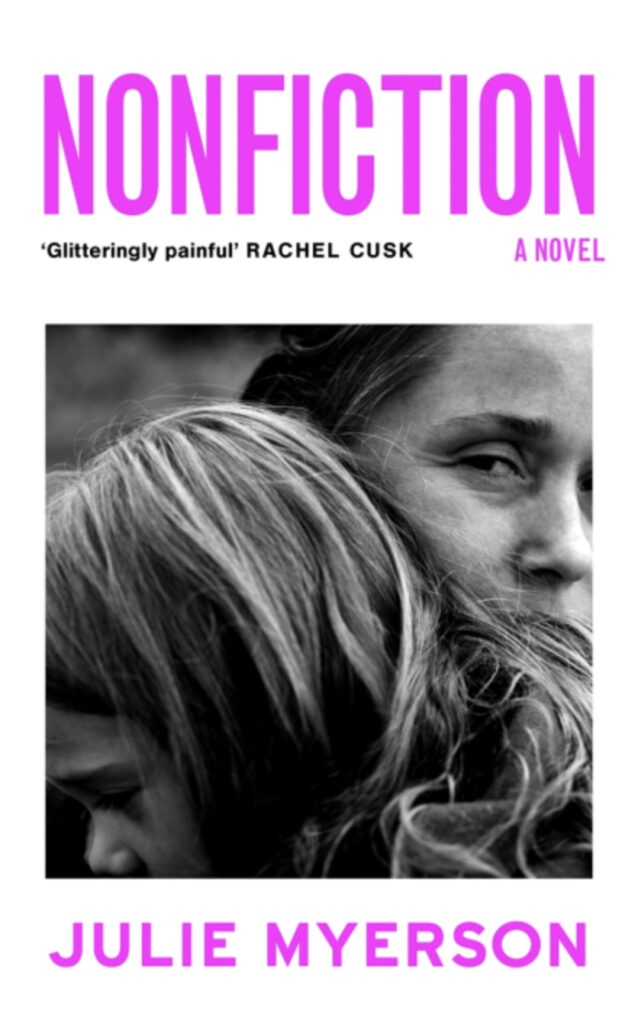

Which brings us to Nonfiction, her new novel.

A woman relates the story of her teen drug-addicted daughter while navigating the last of a contentious relationship with her own mother, just as an old lover rears his pretty head at her most vulnerable. So here’s the thing. Isn’t this just the same story? Yes, it is. But there’s no sin in reworking themes. Joan Didion does this all the time, as does Lucia Berlin, Siri Hustevedt, Karl Ove. Since Myerson wrote The Lost Child, autofiction has become a thing, and so the title is clever.

Is Myerson hiding in plain sight? Yes, and no. There are obviously elements of fiction here, Myerson trying on new hats for size, but the exploration is different. The ending is different. In The Lost Child, she stays sentimental and sweet even at their worst, for example, after her son breaks her eardrum, the family goes out for a jolly dinner. Here, events are treated with more cynicism, more worn down and bitter. There are unspoken infidelities, strange moments of disconnect. This time, Myerson doesn’t try to explain these away. They just are.

In some ways, the book is a companion to The Lost Child, and in others, it’s very much more about motherhood and what it is to be a woman when the pressures of having a child become unbearable. Themes have certainly matured, and in retrospect, Myerson has gone deeper than she would have dared before with this subject.

There is a point, she finds, where pain is all-encompassing, almost irrelevant when it is normalized. The pain becomes a tool for digging. The book bristles with the loss of childhood, both the protagonist’s and her daughter’s. But also, her mother’s. The book turns into an exploration of cruelty, a quest to find the points of no return in a relationship, and the breaking points of others. What makes love unconditional? When does that love fade?

There is something of an issue with the teen daughter character. She remains son-like, a guitar over one shoulder, as Myerson’s son in The Lost Child. Her muscle movement, the way she acts with drugs, all of this remains doggedly male: dirty, careless, and definitively passive-aggressive in a way only sons can be with their mothers. The thin attempt of a veil of fiction by changing the sex of this child doesn’t quite work, and maybe it would have been braver to keep the child as a boy.

Because we’re in different times to when Myerson released The Lost Child. The public misogynistic bullying she faced barely exists in literary circles; Paxman is an old man while Piers Morgan is on his uppers. Since #metoo, women can talk much more safely about their own lives, and own their lives, in a new way. We don’t have to be sainted, we don’t have to be perfect. Decisions we make in the tragedy of a moment are given breathing space and time. And forgiveness.

Does the girl in the book read like a boy somehow? Absolutely not, IMHO. Other than that, smart, lovely review.