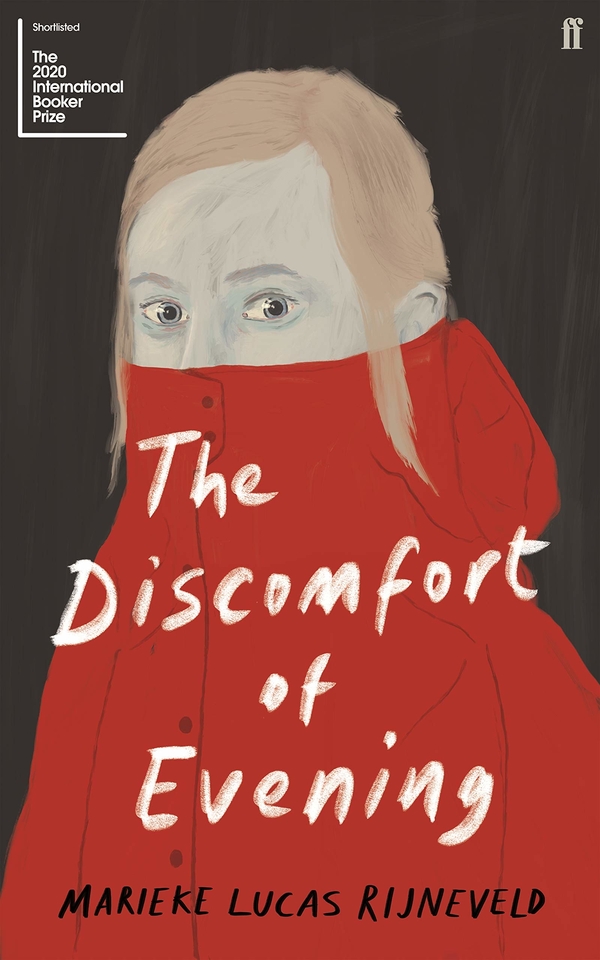

This year’s International Booker shortlist is skewed towards stories told by YA protagonists in extreme emotional distress. Dutch poet Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s book, The Discomfort of Evening is perhaps the most disturbing of these, telling the story of Jas, a young girl locked in a family reeling from the sudden death of her older brother. The story is loosely based on the author’s own childhood when her brother was killed in a skating accident. The writing convinces that it would be impossible to describe such violent and barbaric grief in this way without having first-hand experience of the damage it causes to those left behind.

This year’s International Booker shortlist is skewed towards stories told by YA protagonists in extreme emotional distress. Dutch poet Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s book, The Discomfort of Evening is perhaps the most disturbing of these, telling the story of Jas, a young girl locked in a family reeling from the sudden death of her older brother. The story is loosely based on the author’s own childhood when her brother was killed in a skating accident. The writing convinces that it would be impossible to describe such violent and barbaric grief in this way without having first-hand experience of the damage it causes to those left behind.

Jas lives on a dairy farm with her sister and two brothers. Her parents are simple, hardworking, and religious. They worry about what others will think of them. When her brother is pulled from the lake one night before Christmas, the family suffers with disbelief then extreme guilt, and then they fall into a pattern of cruelty, each with a unique thread. For Jas’s mother, it’s a feeling of self-hatred and nihilism, for her father, it’s outbursts of odd behaviour and distancing. Her sister gets sexual, while her remaining brother tortures and kills animals. Jas will grow to mimic all of these behaviours as the book progresses in a state of shock that prevents her from overly analysing any of her actions, right until the last page.

The writing is beautiful and haunted with a bleak Dutch landscape in winter punctuated with the spartan activities of the farm and church life they inhabit. As a poet, Rijneveld wants us to feel the words in our bones. Details are grim and sharp, sitting heavy with the reader like bleeding wounds. But when the village suffers the tragedy of Foot and Mouth Disease, it’s one sadness too many, and Jas realises that nature is cruel and stark, confirmed in the visceral carnage in her home. Left with the dark conviction she has no agency when her sacrifices don’t stop the pain, much like Hamsun’s protagonist in Hunger repeatedly sabotaging all opportunities for recovery, Jas dances dreamily towards her final, terrible act in what quickly deprecates into a Lars Von Trier sort of scene.

The book will upset anyone who cannot deal with animal cruelty in fiction. I cannot. At times, it becomes titillation. It’s of course hard to take nature so close up, when what lives one line later is dead in terrible circumstances, or maybe slowly tortured, like the pair of starving toads Jas keeps in a bucket under her desk. The overtures of adult desire from their father and the farm’s vet for Jas are revolting, as are the scenes of sexual abuse between the children. But in it all, it’s not difficult to recognise something of our childhood in their thinking, and maybe that’s the hardest to admit.

Some readers will not find much to cheer for in Jas’s cruelty, others will not care for her family as they gradually worsen in their treatment of each other. But Rijneveld’s motif of the old anorak that Jas refuses to take off is there to remind us that Jas is a victim, she’s a kid, that she’s unstable, that she’s suffering. For this reviewer, that wasn’t enough to explain the extreme animal abuse, nor was there much to take home from the story except one emotional beating after then next, albeit exquisitely done. The Discomfort of Evening is an experience that carries into uncomfortable sleep after reading, and maybe that’s the point, and it will be interesting to follow Rijneveld’s trajectory.

Available At

Leave A Comment