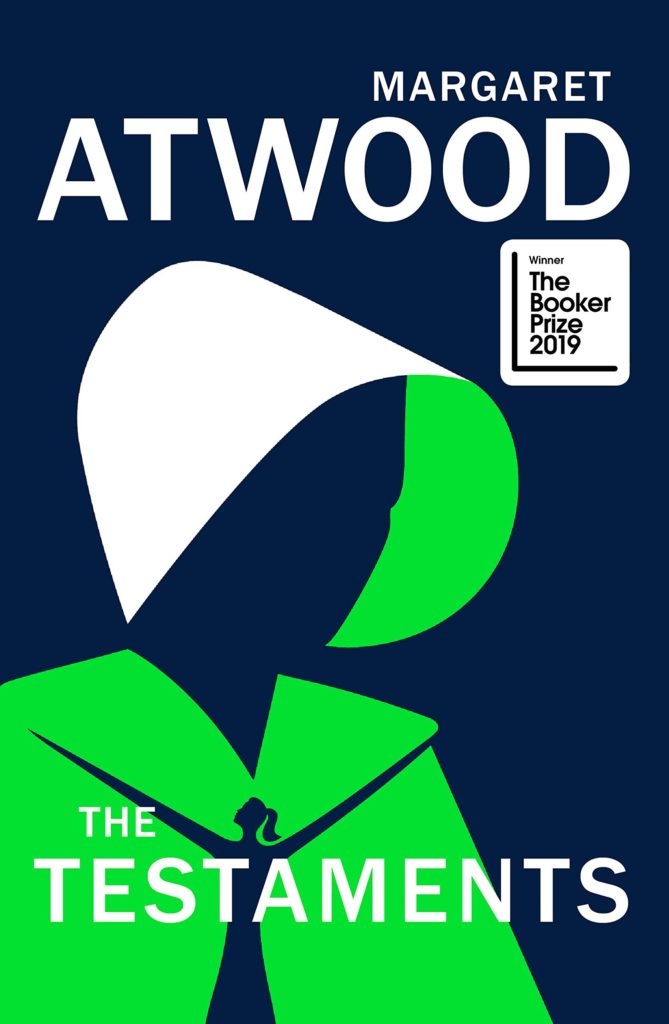

The very first question a writer should ask themselves is, “Does this book need to exist?” When a book is this hyped, it is going to fall a long way if it doesn’t meet the expectations of millions of readers. Dubbed the “sequel” to The Handmaid’s Tale, it was always going to be a challenge for Atwood to write against the brilliant storyline of the adored HBO TV series, adapted from the first book and beyond. Unfortunately, Atwood has answered the question with the wrong answer. The book needed to exist for one reason only: the fans of the TV show wanted more. And that is no way the right answer.

The very first question a writer should ask themselves is, “Does this book need to exist?” When a book is this hyped, it is going to fall a long way if it doesn’t meet the expectations of millions of readers. Dubbed the “sequel” to The Handmaid’s Tale, it was always going to be a challenge for Atwood to write against the brilliant storyline of the adored HBO TV series, adapted from the first book and beyond. Unfortunately, Atwood has answered the question with the wrong answer. The book needed to exist for one reason only: the fans of the TV show wanted more. And that is no way the right answer.

We left the unnamed handmaid of the first book disappearing into the van of the Eyes, scooted away hopefully to a double bluff where she will escape and live on. But if she dies, she has already planted the seeds for a revolution, and she is ready for either scenario. It was a daring and dark ending that left me stunned the first time I read it. It was impossible to know if the handmaid would make it. It was heroic and, well, awesome.

But then came the TV show that picked up where the book left off, calling the handmaid June, as this name was the only name mentioned in the book and not assigned to a character yet. It was not Atwood’s intention, but it was a great idea. For a TV show.

Then Atwood had the idea that The Testaments should answer all the questions we asked ourselves about The Handmaid’s Tale. But this basically destroys all the wonder. I did not need to know what happened to June, or the Aunts, and certainly not Hannah and the baby. By telling me what happened, I now feel I lost something from the first book. That sense of not knowing, therein lies the magic. As Van Houten says in The Fault in Our Stars by John Green when asked what happens after his bestselling novel finishes: Nothing. It’s a novel. The characters are not real. I wish that Atwood had said the same to her agent when pushed to spout these tedious endings.

Having finished The Testaments I feel bereft for that and other good reasons. It’s not very well-written compared to say, Surfacing, which is perhaps Atwood’s best book in terms of style. The Testaments has a cheap sci-fi quality to the writing that drowns in copious dialogue, breaking the show-not-tell rule that writers mostly adhere to when they are at Atwood’s level. And the plot doesn’t make sense. The world so brilliantly carved in the last book breaks its own premise in several ways. For instance, allowing perfectly fertile young women to choose to live as aunts without breeding is totally against the whole reason for Gilead.

I am also bereft because The Booker Prize got swept up in Handmaid fever and forced Atwood in, surely and utterly not based on The Testaments, but because she is Margaret Atwood, creator of Gilead and the HBO TV show The Handmaid’s Tale. The freshly-widowed Atwood surely needed a boost, and I’d be the first to give her a hug. The MeToo movement have taken her as their inspiration. After all, we have all this Trump/Kavanaugh/Epstein business to plow through.

But the issue with being a Sacred Cow is that other Cows less sacred but truly as deserving are overlooked. We have to surely say it how it is in this age. Transparency is key, for all.

So with that, I am going to tell the truth: It is obvious to anyone who has read Bernadine Evaristo’s “Girl, Woman, Other” that Evaristo, an author who clearly ticks all the right boxes in terms of sexuality, gender, skin color, and belief, should have been standing there alone at the ceremony as the winner. Her book is technically and gorgeously written. She should not have been awkwardly sharing the award with Atwood, who also has already won the Booker Prize after all. Knowing what the Booker does for an up and coming writer, it would have been more graceful for Atwood to decline and let Evaristo have her moment in the sun alone (and the other half of the prize money Atwood really can’t need at this juncture).

So when all is said and done, I can’t help feeling The Testaments was probably better off never being written at all, which is miserable, because I really wanted to love it.

Leave A Comment