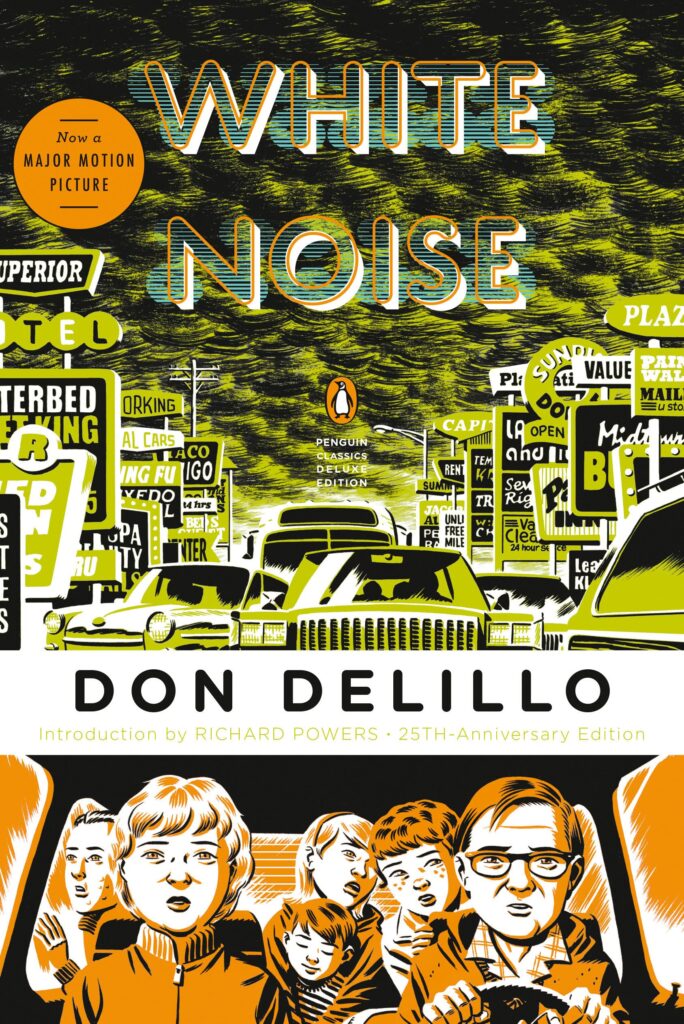

Written in 1984, the eighth novel by one of America’s premier wordsmiths holds up as a masterpiece of postmodern decay despite the horrible movie version Noah Baumbach has recently released.

Written in 1984, the eighth novel by one of America’s premier wordsmiths holds up as a masterpiece of postmodern decay despite the horrible movie version Noah Baumbach has recently released.

When you hear that a film version of an ‘unfilmable’ book is ‘coming out‘, book fans all but groan. But surely, some of us said, Baumbach, of all people, might pull it off? His anxiety-ridden The Squid and The Whale, or the annoying yet charming Frances Ha, with his second wife, Greta Gerwig assuming a De Lillo-style persona in the titular role — surely these chops meant he could get somewhere in the ballpark?

But no. What we got was a very small segment of the book rammed out of context into a bland family frame (we even got a car going over a ridge with the family inside doing a Disney “Whoaoaoaoaoa!”), and this viewer realized (given the sets he built at an obnoxiously astronomical cost for no good reason missing the entire point of the book that blandness is being lionized by modern society; given that he should have really hired Chloë Sevigny for Babette instead of shoe-horning in Gerwig doing her Frances Ha bit yet again which is entirely not Babette’s vibe; given said Disney car bit), that the person that should have really made this film was probably Wes Anderson. Or maybe nobody at all. Because this book is so much richer than what could be crammed onto a screen.

We meet Jack Gladney, an eminent Hitler expert who doesn’t speak German. He’s teaching a unit to a sea of unengaged students at a progressive New School-like university, in a non-descript university town. His burgeoning family of multiple-mothered children and young wife Babette, a therapist for basic skills such as eating and sitting, struggles with the anxieties that the white noise of modern life throws upon them. Both Jack and Babette discover they have the same phobia of dying, while several events roll through town, including a brief episode with The Airborne Toxic Event, made out as the main part of the Baumbach movie but only one of many such chapters in the book. Supermarket and TV jingles filter into their conversations as if at the same level of importance as their own thoughts, while friends and colleagues spout glib truisms. Pop culture is turned into academic subject matter (DeLillo’s prediction from 1984). Meanwhile, Babette seems to be on prescription drugs that are changing her personality, her teenage daughter convinced something more sinister is afoot, a conspiracy to be uncovered with the help of Jack.

Jack is something of an enigma, charming and engaged with a rich backstory, but he’s also lost in his own life. Trying to learn German proves too difficult, and you have to wonder how much of an expert he actually is, considering most Nazi artifacts would be in the language. But given his colleague is studying car crashes in movies and the life of Elvis for his equally pseudo-intellectual class, it seems Jack’s probably at exactly the right sort of institution for his skill set. He’s middle-aged, his kids almost too young for him, as is his nubile wife, although they all rub along together despite fleeting issues. As various events come and go, Jack becomes super-aware of his reality, and as this awareness unfolds, the fear of death suddenly seems curable, within reach.

It would be a poor review that tries to describe any more of the plot. Which is probably why it made such a poor movie. But as a novel, this is a truly engrossing and poignant read. Given this book is now nearly forty years old, it’s a testament to DeLillo’s observation of humans in their unnatural habitat that all the issues Jack and his family live through, such as the industrial destruction of natural resources, climate change (before these were highlighted by Carl Sagan), the multi-national takeovers, and the deification of pop culture, are still just as raw and visceral, if not even more so in the zeitgeist of today than they were when he wrote this novel.

And the last line of the book…oh that last line must be one of the best in the history of writing!

Available At

Leave A Comment